Research

"Nothing in biology makes sense

except in the light of evolution."

T. Dobzhansky (1900-1975)

We develop and use theoretical methods to study proteins

We work at the interface of biology, computer science, mathematics and physics. Our group specializes in computational biology of proteins and combines sequence and structure analysis with evolutionary considerations to facilitate discoveries of biological significance. Two major directions are pursued:

|

This duality, i.e. combination of methods development with biological applications is beneficial for both directions, as we frequently find that existing approaches do not give satisfactory answers to specific biological questions; and availability of experts biologists in our group to validate the results in the process, stimulates methods development.

• Introduction •

What is the most important unsolved problem in computational biology of proteins? Apparently, protein energetics. 1) Protein folding problem (i.e. prediction of spatial structure from sequence); 2) precise modeling of interactions between proteins and of proteins with other molecules; 3) quantitative understanding of enzyme catalysis — are all various incarnations of the same challenge scientists were not able to overcome. Despite significant achievements, the exact solution from the physics perspective is still far from reach.

Bioinformatics approaches offer practically useful shortcuts to these problems. Deduction of protein properties (i.e. 3D structure or function) by homology to proteins with known properties has been most successful. For this method to reach its full potential, the following steps should be perfected. We need to: 1) find homologous proteins, i.e. do a database search; 2) compare them to the protein of interest, e.g. make an alignment; 3) decide on the boundaries of property transfer by similarity, i.e. at what level of similarity a property is shared between homologs, and thus can be deduced for a homolog without available experimental information from experimentally characterized homolog. Most projects in the lab deal with these questions.

Homology and evolution are the central themes of our research. By homology we mean similarity caused by common ancestry, not any kind of similarity. Proteins are homologous if they originated from a common ancestor. Similarity caused by other reasons, e.g. structural constraints on 3D packing, is termed analogy. When similarity is weak, it is not trivial to distinguish between the two scenarios leading to similarities between proteins: homology or analogy, and we are working on this problem.

• Main Research Directions •

The long-term objective of our research is to classify available sequence-structure data on proteins into a biologically relevant, hierarchical system analogous to the one currently used in zoology and botany, and to provide computational tools to maintain and update this classification. Since sequence and structural similarities usually imply functional similarity, such classification is of indispensable value for biologists to aid in experimental design. Combination of various approaches is best for addressing complex problems. Thus the questions we pursue are quite diverse and can be summarized as follows.

|

|

Our publications give more specific ideas about research directions. We also are involved in many collaborations to study individual protein families, predict properties of proteins, help interpret the effects of clinical mutations and assist in data analysis–driven experimental design.

• Research Highlights •

A. Method development

During the last few years, we have been working on improvement of computational methods to assess protein similarity. We mainly concentrated on two levels of similarity between proteins: sequence and structure. We also directly addressed structure prediction as an important application of homology inference.

A.1. Sequence similarity detection methods

Two main steps constitute sequence analysis. First, homologues are found and separated from unrelated proteins; second, these homologues are aligned. We suggested strategies to improve both steps.

A.1.1. COMPASS – comparison of multiple sequence alignments

Compass is a profile-profile aligner based on a solid probabilistic basis.

A.1.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment

In the process of a tedious search for a tool to provide fast and accurate alignments, we developed this program that up until now demonstrated the best alignment accuracy. PCMA combines COMPASS scoring with the consistency strategy of T-Coffee

B.1.3. Sequence design assists homology searches

Sequence diversity in alignments is essential for

profile-based methods. Profile improvement can be achieved by enriching

alignments with more sequences sharing a common fold. These sequences can

either come from sequencing projects, or be designed in silico.

Structure-based design explores small but important covariation between

positions, which is

being ignored by profile methods. We extended the ideas of Koehl&Levitt to

cover sequence-based searches. The design procedure may involve sequences that

are expected to fold into a known structure36,37, or

ancestral sequences reconstructed from a multiple sequence alignment38.

Implementing both strategies, we demonstrated that they assist homology

inference.

To capitalize on these preliminary experiments, we will

combine evolutionary and structural design strategies to produce in silico

sequences for many protein families, and will carry out sequence searches in

the new expanded space.

B.2.

Structure similarity detection methods

None of the numerous methods proposed for structure

similarity search39-42 achieves

what we consider the most fundamental task, i.e. finding structural motifs that

satisfy the general definition of a protein fold: globular units with the same

secondary structure, topology and architecture irrespective of subtle

differences in packing between elements. Such a program should be key in

protein structure-mining. The closest available utility, TOPS43 falls

short, since it checks topology only. While developing a structural motif

search algorithm, we were surprised to find that a method providing broad, yet

accurate secondary structure delineation44,45 was lacking

as well.

B.2.1. PAL8E – delineation of secondary structural

elements

We delineate secondary structural elements using Ca

coordinates in order to generate input for the fold search46. The

elements we define (helices and strands) are linear, so they can be

approximated by vectors; and cover about 85% of residues in the structure, so

they can provide maximum representation in an element-based search. Our program

is predictive by nature, i.e. it does not evaluate the actual existence of

hydrogen bonds as DSSP44, but rather

checks if the general geometry is sufficiently close to provide H-bond presence

in some conditions. As such, PAL8E is robust to coordinate errors up to 1.5Å

RMSD and is more suitable as the first step to finding remote structural

similarities.

B.2.2. ProSMoS – Protein Structure Motif Search

Programs that assess structural similarity compare two

structures to each other and define common regions39-42. Structural

classification experts look for a particular structural motif instead10,47. Most

programs base similarity scores on superposition and closeness of either

coordinates or contacts. Experts pay more attention to the main chain

orientation and general match of secondary structural elements. We developed a

program that emulates an expert48. Starting

from a structure, we use PAL8E46 to

delineate secondary structural elements. A matrix of element interactions (parallel

or antiparallel) and handedness of connections is constructed. All structures

are reduced to matrices that contain just enough information to define a fold,

so the definition is very general and large deviations in coordinates are

tolerated. A user supplies a matrix for a motif, and ProSMoS lists all

structures that exactly match this motif. Application of ProSMoS to several

tasks demonstrated its usefulness49-51.

We have yet to 1) develop a good scoring function; 2)

implement an algorithm that finds partial matches to the motif, and 3) develop

an algorithm to produce a residue-to-residue alignment based on detected motif

similarity.

B.3.

Combination of methods for homology detection: SCOPmap

Likely the most difficult task is to identify whether

proteins with remotely similar structures share a common ancestor9. Done

largely by expert analysis, such work is very time-consuming10,47. To tackle

it computationally, we designed a strategy that checks sequence and structure

similarity statistics using various existing programs, combines their scores,

and attributes a protein structure to a previously defined evolutionary

classification52. Our

automatic method assigns about 95% of proteins to SCOP leaving the rest to

expert analysis. Instances of incorrect assignments near domain boundaries need

more work.

B.4.

Structure modeling methods

After establishing a homology link, the structure of one

protein can be modeled using the other one as a template53. We tried

to improve scoring functions for several specific problems in homology

modeling.

B.4.1. Side-chain modeling

Placement of given side-chains on a fixed backbone

(=packing prediction) is a necessary step towards a realistic protein model54. Careful

refinement of weights for “energy” terms and usage of contact

surface/overlapped volume allowed us to obtain a better side-chain rotamer

predictor55, which has

been used by many other researchers, e.g.56-58.

B.4.2. Sequence design

Finding optimal side-chains for a fixed backbone

(=protein sequence prediction) is a natural extension of the side-chain

modeling problem59. Parameters

refined on a set of high resolution structures correlated well with

experimental data on mutant T4 lysozymes stability37. We used

the designed sequences to assist in remote homology detection.

We plan to 1) incorporate restricted backbone moves in

the design algorithm; 2) as a collaboration with Dr. Zhang, to determine the

X-ray structure of a protein with a new fold that we constructed de novo

from short fragments of the backbone and designed a sequence for with our

approach.

B.4.3. Local structure prediction

Fragment-based structure prediction methods60 explore

“horizontal” (local sequence) information in protein sequences, in contrast to

sequence alignment methods that use “vertical” (positional) information

assuming independence between positions61. To improve

homology detection and sequence alignment construction using local conformation

predictions, we developed a local fragment predictor28.

We plan to add statistical significance estimation of

local profile hits and to incorporate it into alignment algorithms.

B.5.

Methods to evaluate the quality of structural models

Our group was invited to judge predictions in Critical

Assessment of Structure Prediction competition (CASP5)62. Evaluating

thousands of structural models, we found63 that a

consensus method combining many scores generated by various structure

similarity scoring schemes correlates best with manual assessment of models

that has been a standard in former CASPs. Approaches we developed have been

successfully used by different assessors in last year’s CASP6.

C.

Application to biological problems

As our main scientific interest is to find novel remote

homology links between proteins, we applied various computational methods

enhanced with the manual expert analysis to explore sequence and structure

databases.

C.1.

Large-scale evolutionary classification of proteins

The ultimate goal of our research is to classify all

protein domains according to their evolutionary history. Moving towards this

goal, we selected several protein groups for in-depth analysis. These groups

can be structural, i.e. all proteins of a particular fold; functional, i.e. all

proteins of a particular function; or genome-based, i.e. all proteins in a

particular genome.

C.1.1. Fold-based

Small protein domains (20-60 residues) are notoriously

difficult to analyze due to unreliable similarity statistics caused by

insufficient numbers of residues64. In an

attempt to bring order to one of the small protein groups, we classified all

zinc finger structures.

C.1.1.1. Zinc fingers

We define zinc fingers (ZF) as small domains where zinc

contributes to the protein structural core. We classify all ZF structures into

8 fold groups based on structural similarity around the zinc-binding site65. Each

fold-group encompasses 1 to 11 evolutionary families. Prior to our work, there

has been no targeted attempt to comprehensively classify all ZFs. However,

rudiments of such classification existed within general structure databases10,47.

We are currently extending our experience with ZFs over

another very large group of small proteins: disulphide-rich domains.

C.1.1.2. Thioredoxin fold

For larger domains with the core formed by secondary

structural elements, classification could start with ProSMoS search48, as we have

done for thioredoxin fold, an a/b

domain of 6 secondary structural elements50. Our

definition of fold allows circular permutations, i.e. geometric transformations

that link existing N- and C-termini of the chain and introduce new termini at

another point. Since permutations regularly happen in protein evolution66, their

inclusion in the fold definition ensures completeness of coverage. We unify

about 1000 protein structures from 5 different SCOP folds10, and divide

them into 11 evolutionary families. For many of these proteins, structural

similarity to thioredoxin remained unreported.

We are working on classification of RNAse H and Rossmann

folds, and will plan to cover other wide-spread folds, such as Greek-key

immunoglobulin-like, ferredoxin-like and a-folded leaf.

C.1.2. Function-based: kinases

Bringing together all proteins that share significant

functional similarities and looking at the whole group from evolutionary

perspective is informative for understanding both function and evolution67,68. In

addition, such work results in many challenging structure predictions. Our

study of kinases defined as enzymes transferring terminal P-group from ATP to

another molecule is included among the five references69,70. Although

protein kinases are frequently analyzed and classified71, no

comprehensive classification of all kinases, including many families of

metabolic small molecule kinases, existed.

We are extending our experience with kinases on several

evolutionary diverse protein functional classes, such as proteases,

phosphatases and acyltransferases.

C.1.3. Genome-based: human Y chromosome

Computational genomics necessitates annotation of

proteins encoded in complete genomes72. Meticulous

expert-driven study of proteins from a single organism is capable of finding

interesting functional annotations and structure predictions that are missed in

large-scale automatic analyses73. We applied

our experience to human Y-chromosome74 (see one of

the five publications).

We are planning to undertake diligent domain analysis of

all human proteins with the goal of evolutionary classification and structural

prediction, crucial for our understanding of human biology.

C.2.

Studies of individual protein families

This aspect of our work is arguably closest to the bench

and richest in immediate biological applications. Taking an individual protein

and a few of its relatives, we embark upon solving a problem that other

researchers pursue at the bench, namely, we try to find out what that protein

does and how it functions. Many of such cases result in unexpected structure

predictions.

C.2.1. Structure predictions

During the last few years, our studies of two dozen

families resulted in non-trivial and yet confident structure predictions75-90 Many of our

published predictions remain unverified by experimental structures. However,

more structures become available every year. Some of these correspond to

proteins for which we have published predictions. On occasion, structural

biologists discuss our predictions in their publications describing

experimental structures91. Several

such articles are included in the Appendix to this report. So far, not a single

fold prediction reported by us has been found incorrect. Naturally, careful

analysis of alignments reveals that some details of our models are not always

accurate. The most interesting deviation from the model was found by crystal

structures of GyrA and ParC domains92,93 that were

predicted to form six-bladed b–propellers82. Crystal

structures revealed that both domains are indeed comprised of six blades with 4

b–strands

each. However, each blade is involved in a swap of 2 b–strands

with the adjacent blade. This swap could not be deduced by us.

We plan to continue our work on non-trivial structure

predictions of interesting domains.

C.2.2. Homology predictions

The most important aspect of our research is remote

homology prediction, i.e. deduction that proteins A and B share a common

ancestor despite low similarity between them. Although such statement cannot be

verified by direct experimentation, it predicts the possibility of existence of

a protein C, such that both links between A and C, and between C and B are

strong and clear. Thus, homology between A and B can be verified by

transitivity. Protein C may be currently unknown, but frequently its sequence

or structure eventually becomes available. The best argument for remote

homology prediction is made when multiple evidence (sequence, structure, function)

is considered94-103. Despite

remoteness of homology, it could be helpful for the functional understanding of

a protein. One such example, MH1 domain of SMAD, is discussed in an included

publication100.

Our runs of SCOPmap program52 on weekly

updates of PDB frequently produce possible, but not fully justified

assignments. We will be inspecting them to find new non-trivial homology links

that we could support by manual analysis.

C.3.

Fold changes in protein evolution

Analyzing distantly related proteins, at times we see

structural changes large enough to warrant placing homologues in different

folds. We were pioneers in recognizing this universal trend104,105. We try to

understand how protein structures, usually considered to be rigid, change in evolution106,107. One

particular aspect of the problem is distinction between homologues and

analogues, and finding examples of analogues108-110.

Our goal for the next several years is to comprehensively

catalogue all instances of homologues with significant structural differences,

and to understand mechanisms used most commonly by evolution to change protein

structures.

• More info about significant projects •

Fold Change in Evolution of Proteins

From the early days of protein structural biology, researches have been surprised by the resistance of protein spatial structures to evolutionary changes. This remarkable structural robustness combined with the limited number of available 3D structures has lead to a view that the abstract protein structure space is discrete, can be divided into a number of folds, and protein evolution mostly proceeds within the framework of the same fold.

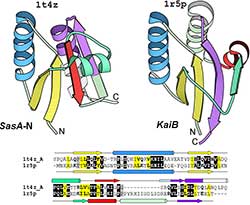

Today, with the rapidly increasing number of protein structures, arguably, the majority of protein structural patterns have been experimentally determined and a new view of structural continuity of folding patterns is starting to emerge. Many examples of proteins with statistically significant sequence similarity, but substantial structural differences, have been documented. Such phenomenon demonstrates the evolutionary bridges between structurally different proteins and profoundly influences our understanding of protein structure evolution. On one hand, the notion that protein structures are evolutionarily plastic and changeable has important applications in protein design and opens new frontiers in engineering proteins that possess desired functional properties, such as a possibility to create proteins with condition-dependent folds. On the other hand, the existence of proteins with similar sequences but different structures hinders homology modeling methods; therefore our ability to detect such cases from sequence is crucial. To study the mechanisms and paths of protein fold change in evolution, we undertook comprehensive comparative analysis of protein sequences and structures, and catalogued the instances of potentially homologous proteins with significant structural differences. Our work revealed that, although such instances are not very common, they are universally observed among proteins of all structural classes, and involve substantial structural changes and rearrangements that may be explained by both small sequence changes, such as point mutations, and large sequence rearrangements, such as non-homologous recombination.

« lessMultiple Sequence Alignment (MSA)

The accurate multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of protein sequences is essential for a wide range of applications from structure modeling to prediction of functional sites [1, 2]. Today, almost every study of a protein starts from MSA construction. MSA of a few homologs reveals patterns of sequence conservation, pointing researchers to important regions in protein sequences. Despite this overwhelming need, MSAs are not very accurate when sequence identity drops below 25%.

Thus, construction of high quality MSA is considered to be the second (after folding) biggest unsolved problem in computational biology. Over the years, our group developed several MSA applications [3-5]. The most recent one is the program PROMALS, which uses secondary structure predictions and a powerful scoring function [4, 6]. PROMALS is the best MSA program according to our test and a recently published review by a pioneer in MSA methods [2]. For the sequences with low similarity, PROMALS is about three times more accurate than the well-known software ClustalW [7]. However, for very distant sequences with identity around 15%, only ~40% of amino acids are aligned correctly by PROMALS. Thus further improvement is needed.

« less